A Profound Comedy

Beethoven: Symphony No. 4 in D Major (1806)

By Alexander Lawler

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth. Many have commented upon its difference: the famous musical encyclopedist George Grove described the symphony as “a complete contrast to both its predecessor and successor…as gay and spontaneous as they are serious and lofty,” whereas composer Robert Schumann delighted in describing the work as “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants.”1 While such descriptions seem to argue against considering the symphony as metaphorically promethean, remember that storm and strife are but one aspect of being promethean. Listen below to Franz Welser-Möst’s take on this quandary:

Jean Paul and the 'inverted sublime"

As Franz described, Beethoven paired the dark, serious, and foreboding slow opening with a spirited, high-octane main section. Like one of Jean-Paul’s novels, this section is dominated by quick shifts in mood and dynamics and, delights in exaggeration. The stark contrast created by this juxtaposition is comic: The opening’s sublime searching reveals nothing like the wrenching internal struggle of the Fifth or the world-conquering heroism of the Third, but, rather, it is music that seems apt for the overture to a comic farce. Beethoven seems to present a humorous counterargument to the earnest seriousness and intensity of works such as the Eroica. As we’ll see, he continues this counterargument in the remaining movements of this symphony

Berlioz’s flowery description of the second movement is a good counterpoint to that provided by Franz.3 Although both focus on different aspects – Berlioz on the wistful, long-breathed melody, and Franz on the connections to ideas of freedom and heroism present in other works by Beethoven – both perceive the movement as in the midst of a symphony that otherwise is devoted to humor. Perhaps this movement provides a contrast to the remaining movements of the symphony, which helps throw the overall theme into sharper relief. Or, perhaps, through its mixture of slow lyricism and an insistent rhythm it offers another alternative to Beethoven’s more bombastic “heroic” style. Whichever and whatever it is, Beethoven leaves it for you to decide. Listen below and see what you think.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 4, II. Adagio

The Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel

Archival Recording: Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, September 1, 1977

The remaining two movements of the symphony return to a frantic, comic tone. In the spirit of Richter’s concept of humor, they might be a reminder, after the second movement’s extended sojourn in sublimity, that joy and freedom are not achieved through serious and sorrowful music alone. The third and fourth movements revel in speed, exaggeration, and mock rhetoric.

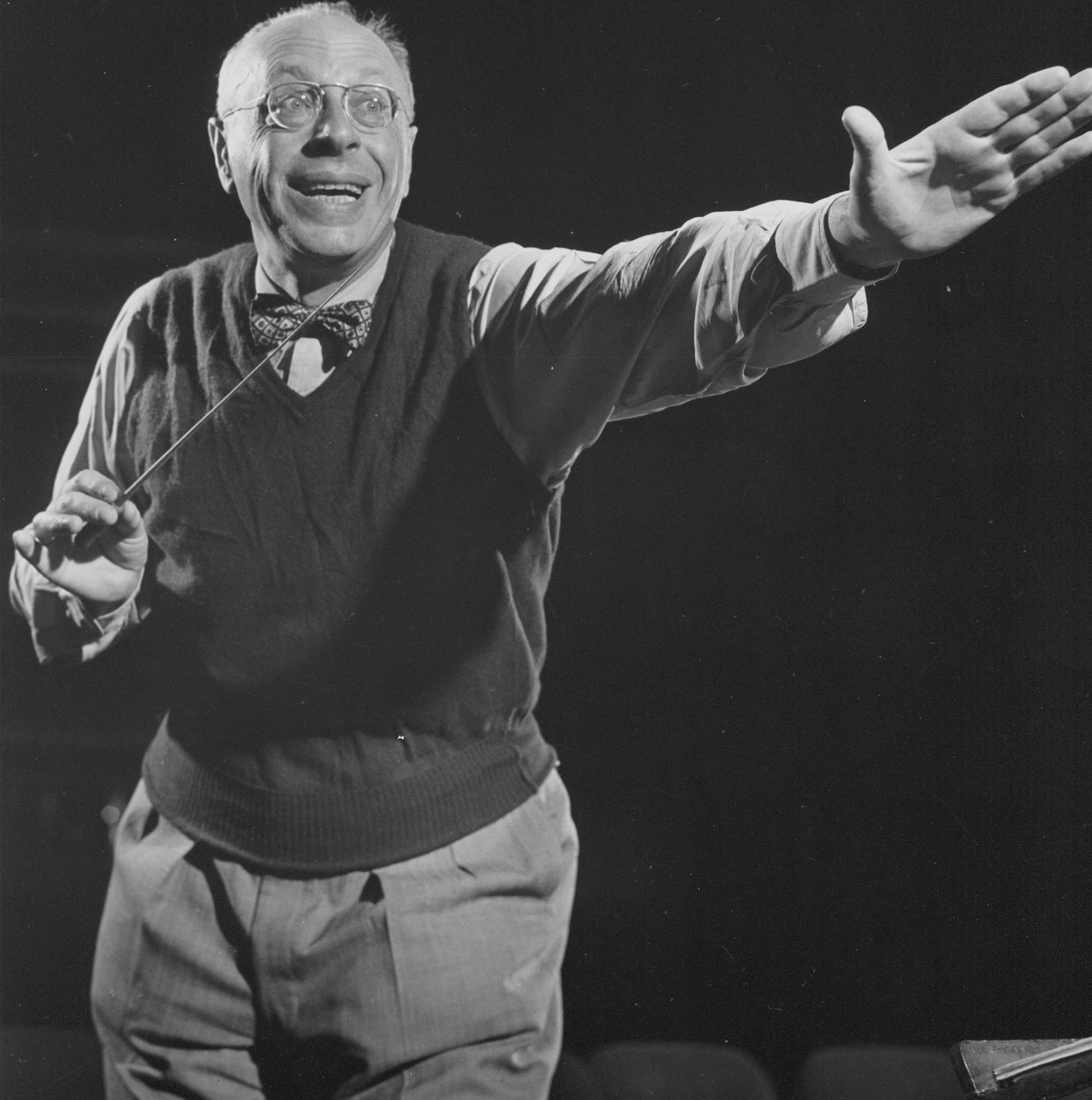

Beethoven: Symphony No. 4, III. Allegro vivace

The Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell

Archival Recording: April 22, 1947

Released: Epic (Columbia), 1947

Beethoven: Symphony No. 4, IV. Allegro ma non troppo

The Cleveland Orchestra, Jahja Ling

Archival Recording: Blossom Music Center, July 2, 1999

- 1 George Grove. Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies (London: Novello, 1896), 98; Lewis Lockwood. Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (New York: Norton, 2017), 80.

- 2 Thomas Sipe. “Beethoven, Shakespeare, and the ‘Appassionata.’” In Beethoven Forum , Vol. 4, edited by Christopher Reynolds, Lewis Lockwood, and James Webster (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 76.

- 3 Hector Berlioz. A Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies, translated by Edwin Evans (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 56.

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Coming Soon

Symphony No. 8

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Coming Soon

Leonora Overture No. 3

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Coming Soon

Symphony No. 9

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Readingf

Symphony No. 2

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Coming Soon